Maybe it's Mary?

A Newly Discovered Hilliard Miniature is being identified as a portrait of Southampton, with a possible link to Shakespeare. There is a better case for someone else.

About a month ago, several papers in the UK carried news of a newly discovered portrait by Elizabethan court painter Nicholas Hilliard. The Guardian headlined the story “Newly discovered portrait may depict ‘fair youth’ of Shakespeare’s sonnets” with a subhead that further suggested, “Earl of Southampton may have given writer the miniature by Nicholas Hilliard, which has defaced heart on its reverse.”

The identification and interpretation was offered in an article published in the Times Literary Supplement for September 5, 2025. The authors include two experts on Hilliard, Elizabeth Goldring and Emma Rutherford, and Shakespeare authority Jonathan Bate. Goldring published the award winning Nicholas Hilliard: Life of an Artist in 2019, Rutherford founded the Limner Company, a consultancy and dealership that specializes in Hilliard miniatures, and Bate has written several books about Shakespeare and his writing. While I have some trepidation about questioning the conclusion of such authoritative experts, I am afraid they have run astray in their desire to link the miniature to Southampton and Shakespeare, and that a much more likely identification can be deduced from the elements of the painting. Perhaps any disappointment will be allayed by the fact that this identification also involves a celebrated writer, a young man thought by many to be the fair youth of Shakespeare’s sonnets and a story of frustrated love.

The first and most obvious problem for this identification is the date offered for the painting. According to Goldring, “The miniature’s style indicates it was painted in the early 1590s.” Hilliard produced dozens of miniatures and some full sized painting of English court figures starting in the 1570s and continuing well into the reign of King James. He was granted a royal monopoly on the production of miniatures by James in 1617, but was jailed the same year and died only two years later. His early work tends to use blue backgrounds, the red velvet with distinctive folds appears after 1590. Apparently Hilliard had trouble representing drapery in this small format, and the way the folds are painted evolved over time. This version reflects the later style seen in the portraits of King James and his family circa 1609. As best I can tell there is nothing that would indicate that this work is from early in the possible time frame from 1590 to 1619. The clothing provides another reason to doubt the early date. The polychrome embroidered linen jacket the sitter wears is a favorite of textile historians and costumers. It is considered highly specific to the period from 1610 to 1620 whence it is known from many portraits and a surprising number of intact garments. The most famous example is the Margaret Layton jacket in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London where it is displayed with a portrait of Layton wearing the jacket by Marcus Gheeraerts the younger dated 1620.

Another example is the William Larkin portrait of Dorothy Carr (now identified as Elizabeth Cary), in the collection of Kenwood house, dated 1614-18, which has bows matching the Hilliard jacket. All the previously known portraits with jackets in this style are attributed to either Gheeraerts or Larkin, so the Hilliard is an anomaly in any event.

While there are examples of similar jackets dating back to the time of Elizabeth, they differ in cut or decoration. It would require a substantial revision of our understanding of period styles to have this distinctive garment appear 20 years earlier than any of the known examples. Why do these authors proffer such an early date? We have many period portraits of Wriothesley, including another Hilliard miniature, this dated in gold, 1594, and indicating the sitter’s age, 20, correct for Wriothesley. There is an obvious superficial resemblance, the hair is similar, both show a love lock hanging over the left shoulder covering the heart, the eyes are similar, both have an irregularly folded red velvet background. However, this is not the wide heart shaped face of the newly discovered painting, it is longer, more masculine. The smaller fallen lace collar folds over a high collar on the doublet with elaborate buttons are all more appropriate for the early 90s.

Both the evolution of fashion and the changes to Wriothesley are clear in this portrait, by John de Critz dated 1600

This is obviously an older version of Southampton, and his beard and face only get longer in later portraits. If the Hilliard is Wriothesley it must be a much younger man. Again, there are a couple elements that are consistent. Both portraits show the same long slender fingers, and the de Critz portrait also shows him wearing bracelets, an unusual accessory on a man.

Hilliard painted his miniatures on the back (traditionally plain white) side of playing card, their values sometimes visible on the reverse of the finished painting. In this case they believe the card was the three of hearts, although only one heart is visible. I think the choice of 3 rather than ace or two is mostly an attempt of these researchers to conjure a romantic triangle as many see in Shakespeare’s sonnets, though I am not sure how they would distinguish among these possibilities.

“Miniatures were inherently private artworks that were frequently exchanged as love tokens,” said Dr Goldring. “This miniature is pasted onto a playing card, which is customary for the time. The reverse of this playing card was originally a red heart, but most unusually, the heart has been deliberately obliterated and painted over with a black arrow. It could, arguably, be a spade - but I think it more strongly resembles a spear, the symbol that appears in Shakespeare’s coat of arms.”

I am not sure why she thinks it is more likely a “spear, as appears in Shakespeares coat of arms” than a spade, as had the symbol actually replicated the spear head from the arms it would have been indistinguishable from the spade symbol traditionally used on playing cards. The sides which flare away from the shaft make this a broadhead arrow. The difference is significant, the arrow is designed to be impossible to dislodge once embedded in its target, insuring that it disables if not kills. Spears (the Shakespeare heraldry image is not a spear but a lance based on its base, but nevermind that) are primary handheld weapons for their wielders, if they remained stuck in an enemy the user would be disarmed for the remainder of the battle.

The broadhead arrow was also a heraldic symbol with a literary connection - it was the sole mark on the arms of the Sidney family, whose members in period include Philip Sidney, the consummate courtier whose tragic death at Zutphen in 1588 made him a national hero.

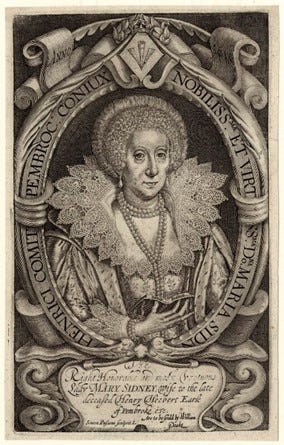

Philip’s sister Mary was remembered as the titular dedicatee of his romance, The Countess of Pembroke’s Arcadia, and for her role editing and publishing her brother’s writing which also included Astrophil and Stella, his sonnet cycle that lit a fad for sonnets in 1590s England, and his Defense of Poesy, a work of critical theory that influenced English fiction writing for centuries. Mary was a writer in her own right, as reflected in the engraving she had made in 1618 which celebrates her as a writer with laurels and swan quills (these play on the way the name Sidney is cognate with the french word for swan and are echoed in the swan motif in her lace collar). The publisher has added “David’s Psalms” to the edge of her book, honoring her most admired work, a translation of the Psalms she began with her brother and completed after his death. At the top of the image you can see the Sidney Pheon. The pheon is distinguished by jagged or engrailed inside edges on the barbs, but these could be omitted (as A. C. Fox-Davies, in his Complete Guide to Heraldry (1909), comments: “This is not a distinction very stringently adhered to.”).

What if we accept the dating suggested by the jacket (1610-1620) and the mark on the back as a pheon, symbol of the Sidney family? As we can see from the engraving above, Mary Sidney Herbert was too old to be the young woman in the image by the time the jacket was fashionable. She did have a daughter Anne but she died young around 1604-5, and would have been a Herbert not a Sidney. Philip had a daughter Elizabeth who married Roger Manners Earl of Rutland, but she too died early in 1612 at 28 so would just barely reach our window for the jacket. There do not appear to be any portraits of Elizabeth, although one might argue a resemblence to the sculpture on her funeral monument in Bottesford. Mary’s younger brother, Robert, on the other hand, had many children who might be the right age for our portrait. In 1596 the same Marcus Gheereart who painted Margaret Layton painted Robert’s wife and children.

Despite appearances, two of these skirted figures are male, William, age 6, is wearing the sword, and Robert the youngest (just one) is to his mother’s right. The inscription identifying him as Lord Lisle and Barbara as a Countess must have been added after his father was made Earl of Leicester in 1618. William died aged 22 in 1612 and Robert would have gained Viscount Lisle as a courtesy title as the oldest surviving male. Robert’s eldest child was his daughter Mary, second from the right, age 8 or 9 in this painting. By the time the jacket in the miniature was in fashion she would be in her early twenties, unhappily married to Robert Wroth. Wroth died a month before the birth of their son in 1614. When the son died two years later Robert’s estate passed to his brother John leaving Mary deeply in debt. Not long after she began an affair with her cousin William Herbert, a family record indicates she bore him two children, although Herbert never acknowledged their paternity. Mary published a long romance, The Countess of Montgomery’s Urania, in 1621, which is generally read as a Roman a clef which relates the story of their romance. It was immediately censored and withdrawn, and her sequel was never published in period (the manuscript is at the Newberry Library in Chicago). William is himself of literary interest as he is the most frequently offered alternative to Southampton as the fair youth of the sonnets. Both men were the subject of intense pressure to marry daughters of Edward de Vere during the 1590s, Southampton to Elizabeth and Herbert to Bridget, thought neither match was ultimately accepted (a decade later William’s younger brother Philip Herbert married yet another de Vere sister, Susan). The argument is that Shakespeare was hired to write the procreation sonnets to favor one match or the other, and fell in love himself with the target. The case for Herbert is buttressed by the dedication to “H.W. the onlie known begetter of these ensuing sonnets”, proponents of Wriothesley have to explain why the initials are reversed. William’s case is also strengthened by the evidence that Shakespeare was writing for Mary Sidney Herbert’s company of actors, Pembroke’s Men during the period when the narrative poems were dedicated to Southampton. I tell the story of William Herbert and Mary Wroth and the possible impact of their relationship on the printing of the Shakespeare First Folio here.

As with Southampton, there are details this painting of Mary shares with the newly discovered Hilliard miniature. Mary has the heart shaped face and curly red hair of the sitter, and her gown is adorned with similar red bows. Although this image is still more than a decade before the jacket was popular, it is not hard to see the girl in this image mature into the figure in the Hilliard as she reached adulthood. And of course she would be connected with the pheon on the back as her family symbol. I would not claim the resemblance and the arrowhead are conclusive, but I think the argument for Mary at least respects the evidence in the miniature much better than the case for Wriothesley.

I have argued that the facial geometry of the figure matches Mary better than the somewhat horse-faced Southampton. I asked my daughter, who works as a digital artist, if she could quantify that claim. She produced the following by superimposing a triangle connecting the pupils and tip of nose in the Hilliard on several known images of Southampton and Mary Sidney Wroth. Scaling the images so that the interpupilary distance matches makes the differences in facial geometry obvious: Southampton’s face is much longer overall, while the heart shape of the Hilliard is nearly perfect match for Wroth in these images (the upper image of Mary is cropped from the family portrait above, the lower is a portrait by de Critz at Penshurst). The image below the Hilliard is another painting by de Critz from the Cobbe Collection at Hatchlands, long identified as a woman (‘Lady Norton, daughter of the Bishop of Winton’), but in 2002 identified as Southampton on the basis of similarity to the Hilliard miniature to its left. The resemblance of the new Hilliard in pose to this one was apparently key to its attribution. However seeing them together illustrates the danger of applying the transitive property to things which are only approximately equal.

I am loath to claim this identification is definitive. A serious effort to identify the figure in the newly found Hilliard would require a careful comparison to the originals of these works, more careful examination of the red background against known Hilliard examples and a thorough reexamination of the 2002 case for the Cobbe Southampton by de Critz. I am not sure there is not a better candidate in the extent portraiture of the period. However, I feel quite justified in stating that Mary Sidney Wroth is a much more likely identification than Southampton,

For more information on the jacket in the image:

https://sarahabendall.com/2021/09/01/seventeenth-century-waistcoats-for-women-jacobean-fashions/

https://theclosethistorian.blogspot.com/2014/10/closet-histories-24-embroidered-jackets.html

https://www.sophieploeg.com/blog/strawberries-and-borage-in-17th-century-jackets/

https://www.sophieploeg.com/blog/birds-bees-embroidery/

http://www.larsdatter.com/jackets.htm