Ovid: the Soul of Shakespeare

Birth of Shakespeare Part 2

Second in a series which presents the first published work of Shakespeare within the context of the literary and political environment of 1590s London. In this post I consider the playfully subversive way that Venus and Adonis retells the familiar story from Metamorphoses in an effort to claim the mantle of Ovid for its author.

As the soule of Euphorbus was thought to liue in Pythagoras: so the sweete wittie soule of Ouid liues in mellifluous & honytongued Shakespeare, witnes his Venus and Adonis, his Lucrece, his sugred Sonnets among his priuate friends, &c.

(Francis Meres, Palladis Tamia, 1598)

For Elizabethan readers any retelling of the stories of the classical gods would immediately recall Ovid, especially if the tale involved a transformation of any kind. The story of Venus and Adonis was in the tenth book of Ovid’s Metamorphoses and would have been familiar to any educated Elizabethan either from the original Latin encountered as a schoolboy or in Arthur Golding’s translation, first printed in 1567. Ovid’s earlier works were generally viewed as too scandalous for grammar schools. His first published work, the Heroides consisted of letters from famous women to their lovers. The next, Amores explores the many facets of love through the poet’s relationship with his own lover, Corinna, who may or may not represent an actual woman. His Ars Amatoria was an instruction manual in the art of love. Its first two books advise men how to seduce and keep women, the third provides guidance for woman hoping to seduce men. Ovid probably intended all these works to parody and critique popular writing of the time as metaliterary explorations of the nature and value of literary works, his choice of subject made it easy for readers to overlook the scholarship for all the sex. While Metamorphoses had plenty of sex, it was mostly the randy doings of gods and therefore at sufficient distance from the fornication of ordinary Elizabethan’s to be acceptable, especially as most stories had a fairly strong moral lesson attached. In any event in gathering all the stories in one place, Metamorphoses provided something of an encyclopedia of ancient Greek and Roman mythology. Elizabethan writing was generally highly allusive, readers were expected to recognize references to the bible, the history and politics of Rome, and classical mythology. Ovid provided the guidebook for the myths.

Ovid’s treatment of Venus and Adonis was itself not a particularly rich source for Shakespeare. The story comes at the end of the tenth book and contains only 80 lines of verse (although it wraps an extended digression into the story of Atalanta). The tenth book is narrated (sung) by Orpheus who offers examples of the tragedy wrought by misguided passions of women (foreshadowing his own death, ripped apart by frustrated admirers at the beginning of the eleventh) and mostly tells the story of Adonis’ lineage, before concluding with his story. The story begins with Pygmalion, who, finding actual women disappointing, sculpts his ideal version. Thanks to a prayer to Venus, his art is made real. Most of book (201 lines) relates the story of Myrrha, a daughter of King Cinyras of Cyprus. Myrrha conceives an unnatural love for her father and tricks him into sleeping with her (perhaps of significance to Shakespeare, Orpheus narrates an internal monologue in which she makes an extended rhetorical argument to justify her intended incest). Disgusted and enraged Cinyras determines to kill his daughter and after she flees pursues her to Asia Minor where in desperation she appeals to the gods for protection and is turned into a tree. The child she conceived with her father months before is born out of her trunk and turns out to be a boy of extraordinary beauty, Adonis. Myrrha as a tree weeps tears of sap which turn into the precious substance myrrh.

Ovid’s Venus and Adonis tells the story of Adonis’ birth and adoption by water nymphs under whose care he grows to young manhood. Venus encounters him on a hunt and, scratched by Cupid’s arrow, falls madly in love with the boy. In Ovid’s tale he does not resist her attentions, but nonetheless insists on resuming his hunt the next morning despite her dire warnings about the dangers of the fearsome beasts that haunt the woods. Adonis leaves for the hunt and Venus flies off in her swan-drawn chariot, but upon reaching Cyprus she senses his absence and returns to find him dead, gored in the groin by an enraged boar. In her grief she transforms him into a flower – the final couplet in Golding’s translation evokes the “darling buds of May” in Shakespeare’s sonnet 18. (I provide the Venus and Adonis excerpt from Golding at the end of this post)

As that the windes that all things perce, with every little blast Doo shake them of and shed them so, as that they cannot last.

As the Francis Meres quote at the top of this essay suggests, the identification of Shakespeare with Ovid went far beyond his use of Venus and Adonis for this first published work. Contemporaries saw a striking similarity in style and literary intent that united the two. In this sense directly comparing the treatments of the Adonis myth misses much of the point: Shakespeare’s Venus is much more Ovidian than Ovid’s. We will need know more about Ovid and his works to understand what that means.

Publius Ovidius Naso (Ovid) was born in 43 BC to an important Equestrian household (the Roman equivalent of knighthood, Equestrians had an obligation to serve in the Roman cavalry and a social station below the Senatorial class, but above the common riff-raff and soldiers). His father planned for him a respectable career as a lawyer, merchant and politician, but Ovid was determined to become a writer. He was fortunate in that respect by virtue of the time that he lived. He was old enough to encounter Virgil, the great official mythologizer of the Augustan Empire, and to follow the elegiac love poets Tibullus and Propertius to whom he is often compared. Ovid shared with his friend Horace a deep interest in the function of literature in society and a tendency to use his writing to question, rather than reinforce, political and cultural authority. In following the great innovators of Roman poetry, he could respond by subtly subverting their work, using the forms and genres they established to explore and comment on the developing culture, politics and literature of Rome. His Heroides, compositions in the form of letters from famous women to their lovers and their response, do represent a genuinely new genre, while borrowing characters familiar from famous epic and tragic works allows Ovid explore them in new ways. In particular the Heroides reveal Ovid’s interest in suasoriae, persuasive rhetoric (particularly legal pleadings), and substituting the character’s voice for his own, both devices employed by Shakespeare in Venus and Adonis.

Ovid’s Amores and Ars Amatoria subvert the popular genres of elegiac love poetry and didactic “instruction” books that provide guidance on various subjects (the Art of War, of Poetry, etc.). By choosing titillating topics and unconventional treatments Ovid softens serious critical engagement with those genre’s and conceals political and social commentary with a veneer of light-hearted parody. We see echoes of the Amores and Ars Amatoria throughout Shakespeare’s poem. The final elegy of book one of Amores provides the quote from the title page, “Vilia miretur vulgus; mihi flavus Apollo; Pocula Castalia plena ministret aqua.” (Let base conceited wits admire vile things, Faire Phoebus leade me to the Muses springs -translation by Christopher Marlowe). In this elegy Ovid proclaims that he, and poets generally are immortalized through their poetry. It is not entirely clear whether Shakespeare is claiming immortal status for himself, or simply associating himself with Ovid and his views on poetry, but either way it speaks to the ambition and self-confidence of Shakespeare as he sees his first work into print.

Whether his stratagem of concealing his serious purpose under sexually transgressive subjects failed or worked too well, just as he was completing the Metamorphoses, Ovid was banished to Tomis on the Black Sea coast of Turkey where he spent the last decade of his life. While his writing otherwise contains much biographical information, of his exile he would only say it was the result of “a poem and a mistake.” Speculated reasons range from offending with the critical subtext of his work to having violated norms with its overt sexual content to knowledge of an attempt to overthrow the emperor to having an affair with the emperor’s granddaughter. He continued to work in exile, producing works that express his longing to return to Rome and the uncompleted Fasti, a survey of Roman festivals intended to join the official mythology of the city and placate his political enemies.

Whatever the cause of his disgrace, Ovid’s work was immediately popular in his own time and remained so after his exile. For medieval scholars it provided an excuse to read and write about sexual themes under the cover of classical provenance. Renaissance readers found a resonance between Ovid’s treatment of transformation and the NeoPlatonist humanism of Marsilio Ficino and so Ovid was a favorite writer of the Renaissance classical revival. The connections between Ovid and Shakespeare which were central to his contemporary appeal were largely forgotten in the late 19th century as Romantic writers reinvented Shakespeare in their own image as a natural genius with little classical learning and no need for classical allusion. We are only now beginning to overcome the artificial boundaries on Shakespeare interpretation that grew out of that effort and its impact on early English academia. (see the excellent work by Colin Burrow in Shakespeare and Classical Antiquity). An early leader in this effort to recover the original understanding Shakespeare in Ovidian terms was the great classical scholar E.K. Rand. His Ovid and the Spirit of Metamorphosis offers a much more in depth and illuminating version of the information in this post and is available in a collection of Harvard essays as a free download from Google Books: https://www.google.com/books/edition/Harvard_Essays_on_Classical_Subjects/HPolGKSAXJcC?hl=en

Continue reading here: Sir Philip Sidney: The Elizabethan Adonis

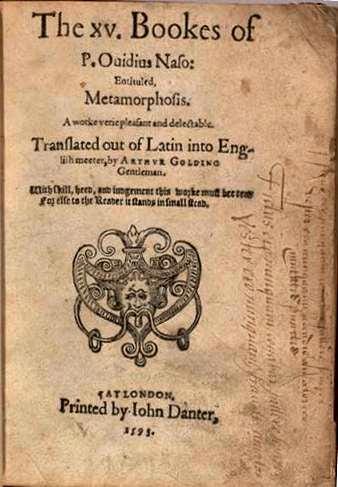

The readily available translation of Metamorphoses in Shakespeare’s time was by Arthur Golding from 1567 but reprinted several times. It is clear from Shakespeare’s text that he consulting both Golding’s translation and Ovid’s original latin in writing the poem.

Venus and Adonis

The misbegotten chyld

Grew still within the tree, and from his mothers womb defyld

Sought meanes too bee delyvered. Her burthened womb did swell

Amid the tree, and stretcht her out. But woordes wherwith to tell 580

And utter foorth her greef did want. She had no use of speech

With which Lucina in her throwes shee might of help beseech.

Yit like a woman labring was the tree, and bowwing downe

Gave often sighes, and shed foorth teares as though shee there should drowne.

Lucina to this wofuU tree came gently downe, and layd

Her hand theron, and speaking woordes of ease, the midwife playd.

The tree did cranye, and the barke deviding made away,

And yeelded out the chyld alyve, which cryde and wayld streyght way.

The waternymphes uppon the soft sweete hearbes the chyld did lay,

And bathde him with his mothers teares. His face was such, as spyght 590

Must needes have praysd. For such he was in all condicions right.

As are the naked Cupids that in tables picturde bee.

But too thentent he may with them in every poynt agree,

Let eyther him bee furnisshed with wings and quiver light.

Or from the Cupids take theyr wings and bowes and arrowes quight.

Away slippes fleeting tyme unspyde and mocks us too our See,

And nothing may compare with yeares in swiftnesse of theyr pace.

That wretched imp whom wickedly his graundfather begate,

And whom his cursed suster bare, who hidden was alate

Within the tree, and lately borne, became immediatly 600

The beawtyfullyst babe on whom man ever set his eye.

Anon a stripling hee became, and by and by a man.

And every day more beawtifull than other he becam.

That in the end Dame Venus fell in love with him : wherby

He did revenge the outrage of his mothers villanye.

For as the armed Cupid kist Dame Venus, unbeware

An arrow sticking out did raze hir brest uppon the bare.

The Goddesse being wounded, thrust away her sonne. The wound

Appeered not too bee so deepe as afterward was found.

It did deceyve her at the first. The beawty of the lad 610

Inflaamd hir. Too Cythera He no mynd at all shee had,

Nor untoo Paphos where the sea beats round about the shore, 1

Nor fisshy Gnyde, nor Amathus that hath of mettalls store:

Yea even from heaven shee did absteyne. Shee lovd Adonis more

Than heaven. To him shee dinged ay, and bare him companye.

And in the shadowe woont shee was too rest continually.

And for too set her beawtye out most seemely too the eye

By trimly decking of her self. Through bushy grounds and groves,

And over Hills and Dales, and Lawnds and stony rocks shee roves,

Bare kneed with garment tucked up according too the woont 620

Of Phebe^ and shee cheerd the hounds with hallowing like a hunt,

Pursewing game of hurtlesse sort, as Hares made lowe before,

Or stagges with loftye heades, or bucks. But with the sturdy Boare,

And ravening woolf, and Bearewhelpes armd with ugly pawes, and eeke

The cruell Lyons which delyght in blood, and slaughter seeke,

Shee meddled not. And of theis same shee warned also thee

Adonis for too shoonne them, if thou wooldst have warned bee.

Bee bold on cowards {Venus sayd) for whoso dooth advaunce

Himselfe against the bold, may hap too meete with sum mischaunce.

Wherfore I pray thee my sweete boy forbeare too bold too bee, 630

For feare thy rashnesse hurt thy self and woork the wo of mee.

Encounter not the kynd of beastes whom nature armed hath,

For dowt thou buy thy prayse too deere procuring thee sum scath.

Thy tender youth, thy beawty bryght, thy countnance fayre and brave

Although they had the force too win the hart of Venus, have

No powre ageinst the Lyons, nor ageinst the bristled swyne.

The eyes and harts of savage beasts doo nought too theis inclyne.

The cruell Boares beare thunder in theyr hooked tushes, and

Exceeding force and feercenesse is in Lyons too withstand,

And sure I hate them at my hart. Too him demaunding why? 640

A monstrous chaunce (quoth Venus) I will tell thee by and by.

That hapned for a fault. But now unwoonted toyle hath made

Mee weerye : and beholde, in tyme this Poplar with his shade

Allureth, and the ground for cowch dooth serve too rest uppon.

I prey thee let us rest us heere. They sate them downe anon.

And lying upward with her head uppon his lappe along,

Shee thus began : and in her tale shee bussed him among

erchaunce thou hast or this tyme hard of one that overcame

The swiftest men in footemanshippe :

(at this point Venus tells the story of Atalanta, a maiden who disdained men and would only yield to one who could best her in a footrace. Hippomenes, despairing of winning fairly, appealed to Venus for help. She provided him with three irresistible golden apples which he used to distract Atalanta and win the race. They married and would have been happy but Hippomenes forgot to honor Venus for her help so she tricked them into making love in a forbidden shrine of Zeus, who turned them into fearsome lions.)

Theis beastes, deere hart : and not from theis alonely see thou ronne,

But also from eche other beast that turnes not backe too flight.

But ofireth with his boystows brest too try the chaunce of fyght:

Anemis least thy valeantnesse bee hurtfull to us both. 830

This warning given, with yoked swannes away through aire she goth.

But manhod by admonishment restreyned could not bee.

By chaunce his hounds in following of the tracke, a Boare did see,

And rowsed him. And as the swyne was comming from the wood

Adonis hit him with a dart a skew, and drew the blood.

The Boare streyght with his hooked groyne the huntingstafFe out drew

Bestayned with his blood, and on Adonis did pursew,

Who trembling and retyring back too place of refuge drew,

And hyding in his codds his tuskes as farre as he could thrust

He layd him all along for dead uppon the yellow dust. 840

Dame Venus in her chariot drawen with swannes was scarce arrived

At Cyprus, when shee knew a farre the sygh of him depryved

Of lyfe. Shee turnd her Cygnets backe, and when shee from the skye

Beehilld him dead, and in his blood beweltred for to lye,

Shee leaped downe, and tare at once hir garments from her brist,

And rent her heare, and beate uppon her stomack with her fist.

And blaming sore the destnyes, sayd : Yit shall they not obteine

Their will in all things. Of my greefe remembrance shall remayne

(Adonis) whyle the world doth last. From yeere too yeere shall growe

A thing that of my heavinesse and of thy death shall showe 850

The lively likenesse. In a flowre thy blood I will bestowe.

Hadst thou the powre Persephonee rank sented Mints too make

Of womens limbes? and may not I lyke powre upon mee take

Without disdelne and spyght, too turne Adonis too a flowre?

This sed, shee sprinckled Nectar on the blood, which through the powre

Therof did swell like bubbles sheere that ryse in weather cleere

On water. And before that full an howre expyred weere,

Of all one colour with the blood a flowre she there did fynd,

Even like the flowre of that same tree whose frute in tender rynde

Have pleasant graynes inclosde. Howbeet the use of them is short. 860

For why the leaves doo hang so looce through lightnesse in such sort,

As that the windes that all things perce, with every little blast

Doo shake them of and shed them so, as that they cannot last.