Reading Mary Sidney

An introduction to her acknowledged works

A reader asked for an introduction to the acknowledged works of Mary Sidney Herbert so that she could compare them with Shakespeare. It has been my intention to provide a repository of links to Sidney materials and this seems like a good place to start.

In her own published work, Mary Sidney pushed the boundaries of acceptable literary work by a woman, but did not transgress them. In translating religious writing (the biblical Psalms of David) she followed a tradition that included Henry VIIIs last queen Catherine Parr (who was her husband’s aunt) and Queen Elizabeth. Translations of works in French by Philippe de Mornay (A Discourse on Life and Death) and Garnier (Antonius but mostly the story of Cleopatra confronting his loss) and the Italian of Petrarch (The Triumph of Death) were considered acceptable for women as well, especially so since she confined her subject to meditations on death in the years following the passing of her parents and brother.

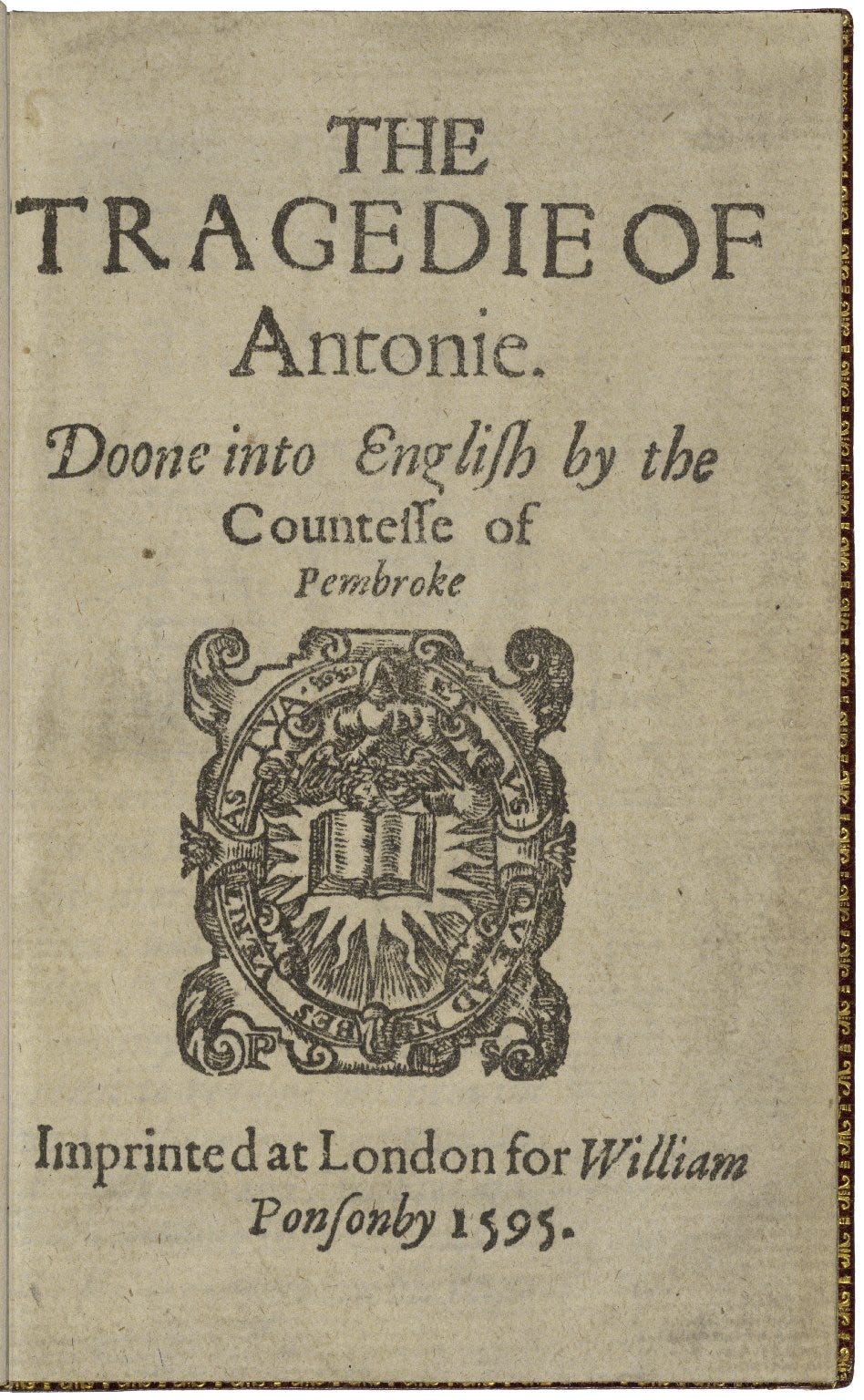

The Philippe de Mornay essay was published together with her translation of Garnier entitled Antonie in 1592. Though modern scholars laud her for breaking boundaries for women in print, this is the only volume of her work published under her name in her lifetime. The Sidney Psalter circulated widely in manuscript (there are currently 19 extent versions known) but despite pleas to share them more widely they were not published until 1823. There is an extent manuscript apparently several generations removed from her original of a translation of Petrarch’s Triumph of Death, the first known effort to preserve the original terza rima, believed to also date to the period after her brother’s death in the late 1580s.

Unlike almost all of the members of her writing circle, Mary left no original sonnets and despite the interest demonstrated by her translations and patronage, no narrative poem or original drama. Shakespeare left no memorial poems or devotional translation so that within genre comparison is not possible. But we can look to word usage, experiments with varying prosody in the Psalms and plays, and the way both apparently like to draw on multiple sources in multiple languages for names, narratives and themes in their work.

While she was better known to history for her role in publishing the works of her brother Philip, she was not responsible for the original publication of any of the three books on which his fame rests either. Arcadia was first published in 1590 from a manuscript furnished and edited by Philip’s friend Fulke Greville and John Florio. Florio is also likely responsible for the 1592 printing of Philip’s sonnet sequence Astrophel and Stella and the 1595 edition of his Defense of Poesy. In each case it took Mary years to secure control of the publication rights. She published her own version of Arcadia in 1593 and a complete works that included all three in 1598. Recently a volume of the 1613 Arcadia has been identified as Mary’s own, with annotations in her hand that were incorporated in later editions, establishing that she continued to exercise control over his works until her death in 1621.

It is a commonplace among Sidney scholars based on references in surviving correspondence that Mary continued to produce her own original works as well and that a substantial portion of these are lost, perhaps to the fires that twice destroyed the Wilton Library (in 1647 and 1889)

Introductions

Poetry Foundation provides a fine introduction to Mary Sidney Herbert with a comprehensive summary of her known works

Mary’s modern biographer Margeret Hannay provided a summary of her life and works for the International Sidney Society, Mary Sidney Herbert, Countess of Pembroke (1561 – 1621) (The Sidney Society webpage also provides links to period works written by members of the extended Sidney family and critical and historical reviews of their impact).

Biography

Hannay’s biography of Sidney, Philip's Phoenix: Mary Sidney, Countess of Pembroke, published in 1990 remains the indispensable resource for her documented history, but is apparently out of print and quite expensive (although inexpensive second hand copies are available with some patience, contrary to the Amazon listing it is not written in Middle English)

Hannay’s 1990 work updated the only previous biography of Mary Sidney by Frances Berkeley Young published in 1912. Young provides the Sidney translation of Petrach’s Triumph of Death in an appendix.

Complete Works

There are two complete works for Mary Sidney, both published in the 1990s;

Hannay, Kinnamon and Brennan (2 volumes)

Gary Waller (6 volumes facsimile)

Both are hard to find and expensive, fortunately free digital versions are available for most of her works on the internet.

Translations

The first publication of Sidney’s literary work was a 1592 volume which combined her translations of Robert Guarnier’s Antonius and of Philip de Mornay’s Discourse of Life and Death both adapted from French sources. While the subject matter reflects the Countess’s mourning in the period after the deaths of her parents and brother, both works introduce important innovations to Elizabethan letters, and both works were sources for Shakespeare (Antonie for Anthony and Cleopatra).

Elizabeth Pentland provides a nice introduction to Mary’s translation of de Mornay’s Discourse of Life and Death which offers substantial personal and political context:

Philippe Mornay, Mary Sidney, and the Politics of Translation by Elizabeth Pentland

Project Gutenberg has a facsimile edition of the first printing of Discourse and Antonius (1592)

The first modern edition of any of Mary’s work was the dissertation research of an early feminist academic from New England, Alice Luce, published as The Countess of Pembroke’s Antonie in 1897 by the Heidelberg University where she earned her PhD.

Petrarch’s Triumph of Death

The Young biography appends Mary’s translation of Book 3 of Petrarch’s Triumphs, closely following the Harrington copy. Gavin Alexander notes that that copy does not follow the Countess orthography and follows a punctuation scheme that does no service to the text and is unlikely to be authorial. He offers a modernized (or perhaps restored edition here: The Triumph of Death (ed. Gavin Alexander)

Psalms

The Sidney translation of the Psalms of David began as a joint project of Philip and Mary. She completed the translation after he died in 1586. Surviving manuscripts and correspondence make clear that Philip had a hand in only the first 43. Mary may have amended or edited those as well as being solely responsible for the others. Beyond their inherent value as exquisite poetry, the Sidney Psalm translations had a transformative effective on English devotional verse. Although they only circulated in manuscript they were well known to Sidney circle writers John Donne and George Herbert. No-one before or after Mary experimented with prosody in the way she does in the Psalter, I think of it as a sampler of English meter and rhyme schemes, which provides the best available preparation for the way Shakespeare plays with changing rhyme and meter in the later plays. See if you do not find the same.

The Sidney Psalter is a bit hard to find online. It was not published until the Chiswick Press edition of 1823. That edition comprised only 250 copies and is not yet available in a digital version. The next publication wasn’t until 1963. Edited by John C. A. Rathmell it only recently entered public domain. Internet Archive provides a less than elegant text. Access to the much better 2009 Oxford World Classics edition requires a free account.

In period the psalter circulated in several manuscript copies. The best of these were produced by Sidney secretary and scribe John Davies. Trinity Dublin has made their copy available in digital facsimile.

Ed Simon offers an overview of the Sidney Psalter which provides some perspective on the innovative excellence of Mary’s work and its impact upon English vernacular devotional poetry.

Gerald Hammond uses Mary’s translation of Psalm 52 to explore exactly how she innovated upon the vernacular psalm form and how her work influenced other writers even outside of devotional literature.

Original Poems

Mary was not permitted to contribute to any of the memorial volumes of verse in honor of her brother, but Philip’s friend Edmund Spenser included an elegeic poem, The Doleful Lay of Clorinda, which he represents as her work within his own memorial poem Astrophel in the collection Colin Clout Comes Again. There is a continuing debate about whether to accept the attribution or to assign the poem to Spenser himself.

The various manuscript volumes of the Sidney Psalter contain three original poems in the paratext materials, a memorial for Philip and two works directly addressed to the Queen for who a presentation volume was prepared.

To the Angel Spirit of the Most Excellent Sir Philip Sidney

The extraordinary folks at Beyond Shakespeare have done a reading of Thenot and Piers