Venus and Adonis and the Legacy of Philip Sidney

The Birth of Shakespeare

(If you are looking for the rest of this story click here)

The Spring of 1593 was an exhilarating time for readers in London. The theatres were closed by a plague which ravaged the city, but the bookstalls of St. Pauls were filled with new issues from some of the greatest writers England ever produced. Not least of these were the pamphlets of satirist Thomas Nashe who gleefully abused the learned but pedantic Harvey brothers in a literary feud that had begun with Martin Marprelate’s attack on the clergy but had taken on a life of its own.

For his latest response to Nashe, Pierce’s Supererogation, Gabriel Harvey summoned his “Gentlewoman Patronesse” to turn the tables on the writer dubbed the young Aretine after the Italian author famed for his vicious and bawdy writing. In the preface dated April 27 he wrote:

“Were that fair body of the sweetest Venus in Print, as it is redoubtedly armed with the complete harness of the bravest Minerva. - She shall no sooner appear in person, like a new Star in Cassiopeia, but every eye of capacity will see a conspicuous difference between her and other mirrors of Eloquence.

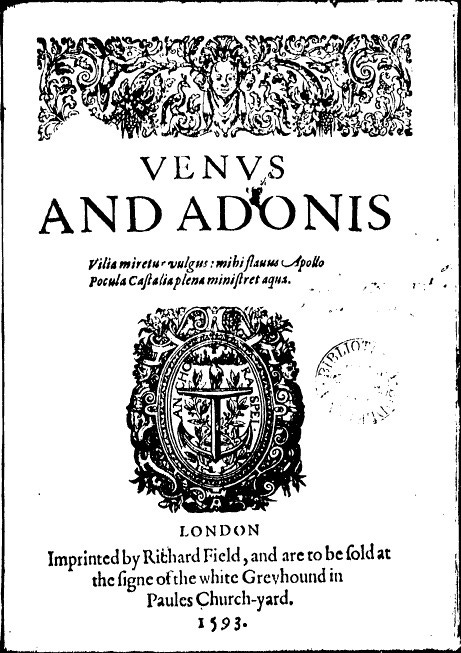

There is little doubt that “She” was Mary Sidney, the beautiful thirty-one-year-old wife of Henry Herbert, Earl of Pembroke, one of the wealthiest men in England. The “harness of the bravest Minerva” invoked the spear-shaking Pallas Athena, associated with Mary in recent dedications by Chistopher Marlowe and Nashe himself (in an unauthorized edition of her brother’s sonnets). The “fair body of the sweetest Venus” refers to the narrative poem Venus and Adonis, registered a week earlier by printer Richard Field but not yet released. When it appeared a few weeks later it caused an immediate sensation. No one had ever written a character quite like the fleshy frustrated goddess who flung herself at the reticent Adonis. It was conventional in Elizabethan poetry that classical Goddesses represent the Queen. For readers who identified the fallen Adonis with Mary’s brother Philip Sidney the identification of this Venus with Elizabeth was both unthinkable and unavoidable. And yet, for all the titillating sexual content, and the political topicality, the poem was also a sophisticated entry into the literary debate over the role of literature inspired by Sidney’s Defense of Poesy. It was the best-selling work of the age. The author was not identified on the title page, but the dedication to the young Earl of Southampton bore a name familiar to us but new to Elizabethan audiences, William Shakespeare.

Centuries of historians have tried and failed to connect Shakespeare and Southampton, as patron, or even as the homosexual lover of the Sonnets. A conflict between Mary Sidney and members of her brother’s circle who joined the faction of Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, after Philip’s death may better explain the dedication.

Mary was the patron of Pembroke’s Men, then touring the provinces performing Shakespeare’s first plays. Venus and Adonis reflects her agenda on multiple levels. She wanted to honor her brother, to fulfil his vision of an English vernacular literature that would “delight and inspire,” defying the Puritan impulse to ban poetry and theatre. She harbored grudges against the Queen and Oxford whom she blamed for Sidney’s tragic death and also against those, particularly Greville, Florio and Nashe that would claim his political and literary legacy to their own ends. That nearly all of these appeared to have cooperated in the publication of Philip’s writing against his expressed desire and without her consent represented a galling provocation. Florio’s position as secretary to Southampton provided a pretext for targeting her response.

While the publication of Venus and Adonis immediately established Shakespeare in the London literary scene, it marked a transition for author and patron in another less positive way. When Field registered the work Mary was the most important literary and dramatic patron in England. She sponsored one of the two acting companies that performed at court that season. Thomas Kyd, Christopher Marlowe, Samuel Daniel and Shakespeare worked together under her direction while she published her own influential translations and edited and published the works of her brother Philip.

Within a year, Kyd and Marlowe were dead, Daniel had moved on, and Shakespeare’s company had become the Lord Chamberlain's Men. Shakespeare’s next works, another narrative poem, the Rape of Lucrece and the play Titus Andronicus, first printed in 1594, both tell the story of a woman violated and silenced. Both characters must die in order to seek justice and restore their honor, a motif known as publishing the corpse.

We are left to speculate- Did the Pembrokes break ties with the theater out of fear after the arrest of Kyd and murder of Marlowe? Was it ordered by the Privy Council (Henry Herbert was as member)? Did Herbert believe his beautiful young wife was having an affair with one or more of her writer friends and wipe out half the writing community of London as a result (there is a potentially lot more history in Shakespeare in Love than people realize). For most of the twentieth century academics tried to separate Shakespeare from the world of court patrons and the literary works they inspired and sponsored. Little by little we are recovering that context as historical research and new perspectives on the works themselves offer windows into the literary and political world of 1590s London.

I tell this story in a series of posts here: Venus and Adonis

About Titus Andronicus, Ben Jonson famously observed in the preface to Bartholomew Fair, published in 1614, that: “He that will swear, Jeronimo, or Andronicus are the best plays, yet shall pass unexcepted at here, as a man whose judgement shows it is constant, and hath stood still these five and twenty, or thirty years.” Meaning that Titus was first performed sometime between 1584 and 1589. That's not too early for Mary Sidney to have written, I suppose (not that there is any evidence whatsoever for that), but it does appear to strain very much the notion of "publishing the corpse."