Venus and Adonis: the Birth of Shakespeare

Introduction

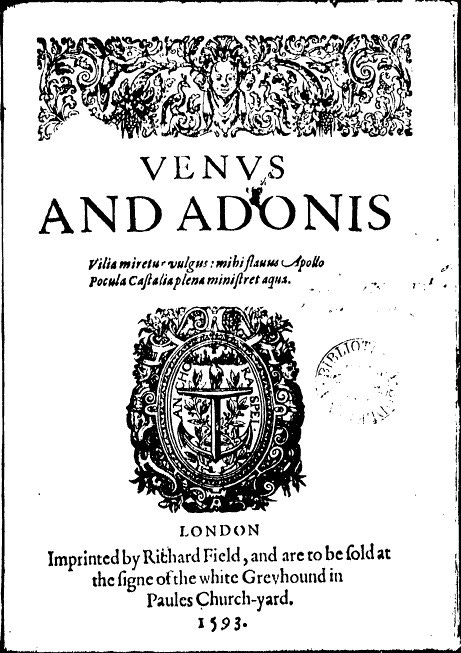

Vilia miretur vulgus; mihi flavus Apollo;

Pocula Castalia plena ministret aqua.

(Let base conceited wits admire vilde things, Faire Phoebus leade me to the Muses springs - translation by Christopher Marlowe)

On April 18th 1593 London printer Richard Field registered “a book intituled Venus and Adonis” with the Stationer’s Guild, establishing his exclusive right to publish the work.

xviijo Aprilis

Richard ffeild Entred for his copie vnder the handes

Assigned ouer to of the Archbisshop of Canterbury

mr Harrison senior and mr warden Stirrop, a booke

25 Junij 1594 / intituled / Venus and Adonis./ vjd S./

G*S

He did not identify the author, but shortly after he offered a quarto edition of a new narrative poem on that theme at his bookstall at the “Sign of the White Greyhound” in St. Paul’s Churchyard. Old St. Pauls (it was destroyed in the Great Fire of 1666) was a gathering spot and hub of the book trade in the center of late Elizabethan England. We know of this initial 1593 printing from a single copy that survives in the collection of the Bodleian Library and because a purchase of the book on June 12th of that year was recorded in the diary of a teller of the Exchequer named Richard Stonley.

Quarto volumes like Venus and Adonis were typically printed in runs of a thousand copies. They rarely warranted second printings but it was immediately apparent that this was something special. Field printed a second edition the following year, then sold the rights to the work to John Harrison in June as noted in the margin of the Stationer’s Guild entry. Harrison printed yet another edition in 1595. There were five more printings within ten years, a total of sixteen known editions of Venus and Adonis dating before 1640 make it by far the best-selling book of the golden age of English literature.

The primary source of this popularity was signalled by the quote on the title page; while Christopher Marlowe’s translation suggests that this is some highbrow literary work, sophisticated readers would recognize the source, Ovid’s scandalously erotic Amore’s. They probably would not have recognized the name of the author, which did not appear on the title page in any event. Still, turning the page they would find at the end of the dedication to Henry Wriothesley, Earl of Southampton, the first appearance in print of the name William Shakespeare.

Of Shakespeare’s works only the two narrative poems, Venus and Adonis and the Rape of Lucrece which followed in 1594, have paratexts (preliminary materials like the quote and dedication) written by the author. Indeed, these two early poems are believed to be the only ones in which the author participated in the publication. Quarto editions of plays later identified as by Shakespeare began to appear in 1594 with Taming of the Shrew and Titus Andronicus, but these only identified the acting companies that performed them, the name Shakespeare did not appear on a play until 1598, when Loves Labors Lost was printed as “newly corrected and augmented by W. Shakespere”. That same year Francis Meres’ commonplace book Palladis Tamia, Wit’s Treasury identified Shakespeare as the author of 12 plays including the lost (or possibly renamed) Loves Labors Won. All of these quartos appear to be either pirated from viewings of the plays or the result of the Lord Chamberlain’s Men selling their play scripts. None are believed to have been published with the participation of the author and none have any of the customary dedications from the author to his patrons or to the author by rival poets that might reveal something about Shakespeare and his literary circle. The publication of the Sonnets in 1609 is believed to be unauthorized and perhaps even suppressed, and the First Folio collection of plays from 1623 was published years after the author’s death. As a result, the dedication to Wriothesley has been the subject of endless examination and speculation about their relationship. In subsequent posts I will offer my own explanation of why Shakespeare chose Southampton for the dedication of the poems and what it reveals about the literary scene of early modern London.

The poem itself contains 1194 lines arranged in 199 sexains (or sextains – verses of six lines each) of iambic pentameter, each organized as a quatrain rhyming abab followed by a rhyming couplet (cc). Spenser had used the form in the Shepherd’s Calendar published some years previous so it was established as a vehicle for pastoral poetry in English vernacular. While Shakespeare chose a pastoral setting and verse form for his work, his subject, the attempted seduction of the beautiful boy Adonis by a comically determined and frustrated Goddess of Love placed it firmly in the genre of epyllion or short epic, a form popular in period with examples by Thomas Watson (Amyntas) and Christopher Marlowe (Hero and Leander) among others preceding Shakespeare’s Venus (although Marlowe’s poem was not published for some years after his violent and untimely death in 1593 just as Venus went to print). Shakespeare’s work is distinguished by the beauty of the poetry, the vividness of its imagery and the playfully subversive way that it retells the familiar story from Ovid, and engages with the literary and political currents of 1590s London.

In this series of essays, I consider what contemporaries would have brought to their reading from classical and recently published antecedents. I will also explore Shakespeare’s relationships to patrons and other writers that might throw light on his motivation and intent in making this the work that launched him onto the literary scene. In particular I will reveal how Shakespeare’s early works emerge from a political and literary conflict between Mary Sidney Herbert, Countess of Pembroke and members of Philip Sidney’s circle who supported Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, and how Shakespeare’s work reflects Mary’s agenda to memorialize her brother Philip, to claim his political and literary legacy and fulfill their joint vision for English vernacular literature. Finally I consider evidence from the works and contemporary references that suggests the author is not the man from Stratford whose birth is celebrated today but rather Mary herself writing under a pseudonym widely recognized by her contemporaries.

While there are good editions of the poem available in print, I particularly like a couple of digital resources:

Internet Shakespeare is a non-profit which offers various versions of the plays and poems. They have both a modern language version and an original spelling transcription (with hyperlinked glossary) of the 1593 first edition as well as providing access to a facsimile of the first edition, all available here.

Google Books offers a free digital download of Charlotte Porter’s edition of the poem which provides a useful summary of sources and contemporary reactions as well as the text of the original edition. Porter is herself a fascinating figure. Check out her Wikipedia entry for more on her.

The story of Shakespeare’s emergence with Venus and Adonis continues with :Ovid: the Soul of Shakespeare

So we will all move up our celebrations from the 23rd to the 18th (not that I ever celebrated the 23rd) in honor of the eventual paratext printings! Fascinating. There is one reference I did not understand, "while Christopher Marlowe’s translation suggests that this is some highbrow literary work, sophisticated readers would ..."