Wits to Read: Francis Meres and Shakespeare’s Small Latin

Ben Jonson on Shakespeare Part 3

Continuing a close reading of Ben Jonson’s FIrst Folio encomium to William Shakespeare, I explore Jonson’s promise to the author “thou art alive still, while thy Booke doth live, And we have wits to read, and praise to give.” I argue that wits is a reference to a period commonplace book, Francis Meres’ Palladis Tamia, Wits Treasury, and that Jonson uses that book as a key to reveal the identity of the author, Mary Sidney Herbert, Countess of Pembroke and mother to the “illustrious paire of brethren” William and Philip Sidney to whom the book is dedicated.

Wits to Read: Francis Meres and Shakespeare’s “Small Latin”

In the Ode “to my beloved the author” which prefaces the First Folio of Shakespeare’s works, Ben Jonson promises the author, thou art alive still, while thy Booke doth live, And we have wits to read, and praise to give.[1] This is traditionally glossed as a conventional assertion that the author will achieve immortality through the enduring popularity of his work, flattering of Shakespeare to be sure, but of no particular significance. However, Jonson’s promise is unconventionally conditional. That the author will be remembered while the work is read is tautological rather than prophetic. But Jonson asserts that even more is required; we will also need “wits to read” to preserve the author’s memory, even if the works endure. The requirement that readers approach works actively and intelligently is a constant in Jonson’s work. His collection Epigrams begins with a two-line poem To the Reader that implores,

Pray thee, take care, that taks’st my Book in hand,

To read it well: that is, to understand.[2]

In the folio eulogy itself Jonson warns of the dangers of ignorant readers misinterpreting his words.

For seeliest Ignorance on these may light,

Which, when it sounds at best, but eccho's right;

Or blinde Affection, which doth ne're advance

The truth, but gropes, and urgeth all by chance;

Fortunately for modern scholars puzzling out Jonson’s meaning, he tells us exactly what we need to remedy our deficiency. Both “Wits” and the lists of contemporary and classical writers that follow would have brought to mind Francis Meres’ Palladis Tamia: Wits treasury being the second part of Wits common wealth[3] for Jonson’s readers.

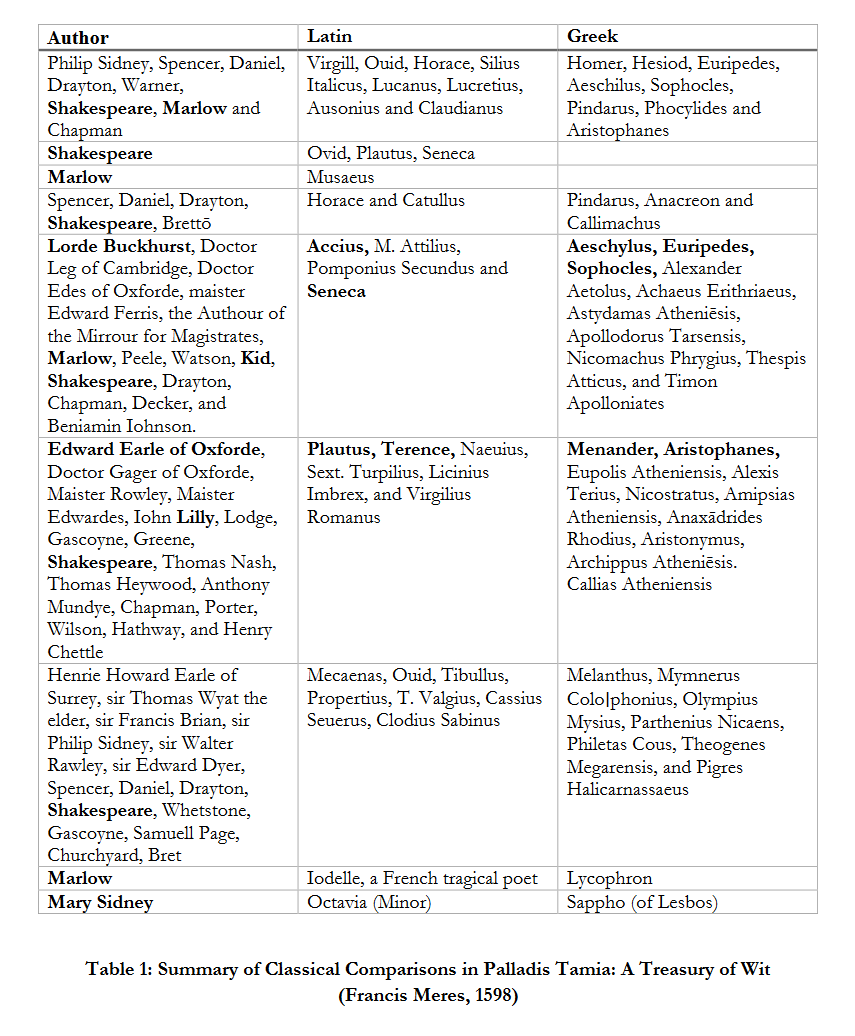

Francis Meres was a cleric who received Masters degrees from both Cambridge and Oxford in the early 1590s. Meres is remembered for his commonplace book, Palladis Tamia: Wits Treasury, published in 1598 and reprinted several times in the succeeding century. Commonplace books like Palladis Tamia were popular in Elizabethan England. They served as compendiums of common wisdom and frequently quoted passages for readers who might struggle with the demands on memory and scholarship created by the richly allusive writing of the time. Ted Tregear’s Anthologizing Shakespeare, 1593 to 1603 provides a fascinating look into early modern use of such books to by examining period annotations. Meres is familiar to modern scholars because it contains a section of comparisons between ancient and early modern writers, full of details about his contemporaries writing and lives. It also provides the earliest testament to William Shakespeare as a playwright, attributing to him a eight early plays for which we have no prior record or which were previously only attributed to the company of players[4] (Originally Pembroke’s Men, later, Sussex’, Derby’s, or the Lord Chamberlain’s as their patronage evolved). Jonson’s “Wits” reference and subsequent lists of writers old and new invites the reader to find the passages in Meres that correspond with the text in the poem and read them together to discover his meaning.

Jonson references three distinct passages in Meres. The stanza following “wits to read and praise to give” implies that the author is an aristocrat and not the commoner reflected in Shakespeare’s place in Meres lists of best for comedy and tragedy. Disproportioned was used in period to denote persons of substantially different station, a commoner with a nobleman. It could also denote sexual distinctions; a man was disproportioned as a woman. Note how the language in the passage reinforces the Meres identification; mixing Muses is exactly what Meres does, and the line ends yeeres and peeres rhyme his name.

That I not mixe thee so, my braine excuses ;

I meane with great, but disproportion'd Muses :

For, if I thought my judgement were of yeeres,

I should commit thee surely with thy peeres,

And tell, how farre thou dist our Lily out-shine,

Or sporting Kid or Marlowes mighty line.

Jonson tells us that if he, like Meres, had ranked Shakespeare among his peers, he would place him far above Lily and Kid and Marlowe. Peeres in this line is the key to unlocking Jonson’s meaning. Meres proclaims:

“the best for Comedy amongst vs bee, Edward Earle of Oxforde, Doctor Gager of Oxforde, Maister Rowley once a rare Scholler of learned Pembrooke Hall in Cambridge, Maister Edwardes one of her Maiesties Chappell, eloquent and wittie Iohn Lilly, Lodge, Gascoyne, Greene, Shakespeare, Thomas Nash, Thomas Heywood, Anthony Mundye our best plotter, Chapman, Porter, Wilson, Hathway, and Henry Chettle.”[5]

This is not a list in order of ability unless by an extraordinary coincidence. The men in this list are in strict order of social precedence. The Earl of Oxford is by tradition also Lord High Chancellor. Following Oxford are Doctors and Masters of Oxford and Cambridge Universities, then Lilly, Lodge, Gascoyne and Greene before Shakespeare and other commoners writing for the stage. Gascoyne and Greene come ahead of Shakespeare because they are dead at the time of Meres’ writing. Lodge is a Doctor of Medicine, having abandoned writing, and Lyly has chosen an even more disreputable profession than playwright; he is a member of Parliament in 1598.

Similarly, Meres lists “our best for Tragedie, the Lorde Buckhurst, Doctor Leg of Cambridge, Doctor Edes of Oxforde, maister Edward Ferris, the Authour of the Mirrour for Magistrates, Marlow, Peele, Watson, Kid, Shakespeare, Drayton, Chapman, Decker, and Beniamin Iohnson.” Note again that throughout precise order of precedence is maintained from the most noble Lord Treasurer Buckhurst to the basest writer in England, Jonson himself. Again, the writers that precede Shakespeare, Marlow, Peele, Watson, and Kid are all dead when Meres is writing in 1598. In order to place Shakespeare “far above Marlow and Kyd”, he would need a title or an advanced university degree.

Small Latin and Lesse Greek

The next couplet is among the most famous and most misunderstood in all of English literature:

And though thou hadst small Latine, and lesse Greeke,

From thence to honour thee, I would not seeke

For names; but call forth thund'ring Aeschilus,

Euripides, and Sophocles to vs,

Paccuvius, Accius, him of Cordova dead,

To life againe, to heare thy Buskin tread,

And shake a stage: Or, when thy sockes were on,

Leave thee alone, for the comparison

Of all, that insolent Greece, or haughtie Rome

Sent forth, or since did from their ashes come.

Whole books[6] have been written attempting to interpret “thou hadst Small Latine and Lesse Greeke” and what it tells us about Shakespeare’s education, biography, and fluency. Few have noticed that the line continues – “from thence to honour thee, I would not seek for names.” Small Latine and Lesse Greeke are names, specifically the names of those ancients Meres compares to Mary Sidney:

Octauia, sister unto Augustus the Emperour, was exceeding bountifull vnto Virgil, who gaue him for making 26 verses, 1,137 pounds, to wit, tenne sestertiæ for euerie verse (which amounted to aboue 43 pounds for euery verse): so learned Mary, the honourable Countesse of Pembrook, the noble sister of immortall Sir Philip Sidney, is very liberall vnto Poets; besides, shee is a most delicate Poet, of whome I may say, as Antipater Sidonius writeth of Sappho,

Dulcia Mnemosyne demirans carmina Sapphus,

Quaesiuit decima Pieris vnde foret.

(Sweet Mnemosyne, sweetly sings Sappho,

No wonder that she is called ‘The Tenth Muse.')[7]

Octavia, sister unto Augustus, was Octavia Minor, literally small. Sappho is of course of Lesbos. Hence Mary Sidney had from Meres small Latine and Lesse Greeke rather than the great writers that were due her as the author Shakespeare. Jonson ensures the point is not lost by calling forth the many that Meres lists as the greatest of Greece and Rome, “As these Tragicke Poets flourished in Greece, Aeschylus, Euripedes, Sophocles … and these among the Latines, Accius, Seneca (he of Cordova)” and, “for Comedy among the Greeks are these, Menander, Aristophanes, … and among the Latines, Plautus, Terence,”[8] … and compares to Shakespeare among other English writers. Mary Sidney is not included in those lists, not even the ones that highlight translations, for which she had already acquired a reputation. Instead, she is treated separately in the brief section of great and noble patrons along with Queen Elizabeth and King James of Scotland. The table above highlights all of the writers mentioned by Jonson, as well as all who have been proffered as author of Shakespeare’s works and the classical comparisons offered by Meres. For nearly all, Meres construction of lengthy lists results in many names associated with each early modern writer; for Shakespeare there are 58. No other significant author is compared with only two, let alone two that could be characterized as small Latin and less Greek. There is simply no other match for Small Latine and Lesse Greeke in Meres; it uniquely identifies Mary Sidney.

In his survey of renaissance literary criticism published in 1908, J.E. Spingarn did find another match for Jonson’s line[9]. In d’Arte Poetica (1564), Antonio Minturno called out certain writers who had “little latin and less Greek” and, as a consequence, thought Seneca a superior tragedian to Euripides and Sophocles. That Minturno by this intended Scaliger and Cinthio, the most prominent writers to profess this view and among the most respected scholars of sixteenth century Europe[10] puts a very different cast on the meaning than the limitations of the grade school education attributed to William of Stratford. The substance of Minturno’s comment fits Sidney as well. As we have already seen, Scaliger was the primary source for Philip Sidney’s Defence of Poesy, with which Jonson aligned Shakespeare in the first part of his poem. In addition Mary Sidney was specifically identified with the effort to incorporate Senecan tragedy into the English stage. Mary Sidney was the first English woman to publish a play under her own name, a translation of Robert Garnier’s Antoine. The French Garnier, a friend of her brother Philip, used Senecan style drama to offer veiled political commentary on the fraught and religiously charged environment of late sixteenth century Europe. His Antoine was a closet drama, intended for informal presentation in homes of aristocrats rather than for the public stage. Mary’s translation, printed in 1595, is considered a primary source for Shakespeare’s Anthony and Cleopatra. Sidney’s encouragement of Thomas Kid[11] and Samuel Daniel[12] to follow her lead with their own translations from Garnier made Sidney the leading advocate of Senecan closet drama in the 1590s. It is not unlikely that Jonson would have connected the Minturno line with Sidney and found the Meres pairing a serendipitous opportunity for clever wordplay.

It is also possible that Meres himself had Minturno in mind, and there is more to the Sidney epigram than simply comparing her to the most famous female patron and poet of antiquity. Octavia was not generally famous for her patronage of poets. The generous gift to Virgil was for memorializing her son Marcellus in the passage Virgil read from the Aeneid at the boy’s funeral. In his Consolation for Marcia, Seneca contrasted the excessive grief of Octavia with the stoicism of Augustus’ wife Livia facing the death of her son, Drusus[13]. Sidney famously secluded herself for two years after both her parents and brother died within a few months in 1586. After she returned to the court she edited, finished and published Philips writings, and patronized writers who wrote in his memory. In his dedication to his Senecan closet drama Cleopatra, written in the style of Garnier and dedicated to the Countess as a sequel to Antonie, Samuel Daniel recognized Mary’s efforts to continue her brother’s defense of Poesy against the Puritan opposition,

Now when so many Pennes (like Speares) are charg’d,

To chase away this tyrant of the North;

Grosse Barbarisme, whose power grown far inlarg’d

Was lately by thy valiant brothers worth

First found, encountered, and provoked forth:

Whose onset made the rest audacious.

Whereby they likewise have so well discharg’d

Upon that hideous Beast incroching thus.

It is clear that Daniel is referencing a passage in which Philip quotes Joseph Caesar Scaliger, “Qua authoritate barbari quidam atq; hispidi abuti velint ad poetas e rep. Exigendos.” (There are some barbarians who would exile poets from the republic on the authority of Plato). Sidney wrote the Defence of Poesy in response to Stephen Gosson’s School of Abuse, an attack on the public stage, and its players. Jonson references the same metaphor in the folio eulogy, “Looke how the fathers face lives in his issue, even so, the race of Shakespeares minde, and manners brightly shines in his well toned, and true-filed lines: in each of which, he seemes to shake a Lance, as brandish't at the eyes of Ignorance.”

The latter referent for Sidney in Meres also offers a connection to Shakespeare. Sappho was well known to Elizabethans, but mainly through the references of other writers who extol her and her works. Antipater of Sidon in the second century BCE imagines Mnemosyne’s surprise that “the mortals have a tenth Muse” in the figure of Sappho (Μναμοσύναν ἕλε θάμβος, ὅτ’ ἔκλυε τᾶς μελιφώνου / Σαπφοῦς, μὴ δεκάταν Μοῦσαν ἔχουσι βροτοί, Anthalogia Palatina 9.66)[14]. Meres’ Latin translation of the original Greek substitutes sweetness for surprise. We don’t have to look far for a matching reference. Only a few lines earlier Meres writes,

As the soule of Euphorbus was thought to liue in Pythagoras: so the sweete wittie soule of Ouid liues in mellifluous & honytongued Shakespeare, witnes his Venus and Adonis, his Lucrece, his sugred Sonnets among his priuate friends, &c. As Epius Stolo said, that the Muses would speake with Plautus tongue, if they would speak Latin: so I say that the Muses would speak with Shakespeares fine filed phrase, if they would speake English.

Moreover, one of the few fragments of Sappho’s poetry that was available to Elizabethan readers was her lamentation of Aphrodite for Adonis[15]. Is Meres intimating that Mary Sidney is the English Muse speaking with Shakespeare’s honeyed tongue?

Shakespeare Responds to Meres: Henry IV part 2

In his 2015 book, Shakespeare’s Verbal Art,[16] William Bellamy identifies Act 2, scene 4 of Henry IV part 1 as an extended response to Meres’ characterization of Shakespeare. The Folger summary of the scene[17] simply notes that “At a tavern in Eastcheap, Prince Hal and Poins amuse themselves by tormenting a young waiter while waiting for Falstaff to return.” The waiter (or drawer, as Shakespeare calls him, a tapster’s assistant or barkeep) is named Francis and Prince Hal indulges in extended wordplay around a “pennyworth of sugar, clapped even now into my hand by an under-skinker, one that never spake other English in his life than “Eight shillings and sixpence” and “You are welcome,” with this shrill addition, “Anon, anon, sir! Score a pint of bastard in the Half-Moon,” or so.” Hal commands his companion Ned Poins, “But, Ned, to drive away the time till Falstaff come, I prithee, do thou stand in some by-room, while I question my puny drawer to what end he gave me the sugar; and do thou never leave calling “Francis,” that his tale to me may be nothing but “Anon.”

Prince. Nay but harke you Frances, for the sugar thou gauest me, twas a peniworth, wast not?

Francis. O Lord, I would it had bin two.

Prince. I will giue thee for it a thousand pound, aske me when thou wilt, and thou shalt haue it,[18]

The rhyming connections to Meres (beers is implied by drawer and Hal asks how many yeeres his indenture will run) and the sugared compliments he offers to both Shakespeare and Sidney could make this a simple jibe in return for a backhanded compliment, but the repetition of “anon” and the teasing offer of a thousand pounds with its echo of Octavia’s gift to Virgil create an intertextual identification in precisely the same way as Jonson does a quarter century later. Poins suggests as much a few lines later.

Poins. As merry as crickets, my lad. But hark ye; what cunning match have you made with this jest of the drawer? Come, what’s the issue?[19]

Nature’s Family

Meres provides Jonson one more opportunity to point to Mary Sidney, which accounts for the intervening lines that encompass “not for an Age but for all time” and conclude with other writers “Not of Nature’s family”.

Tri'umph, my Britain, thou hast one to show

To whom all scenes of Europe homage owe.

He was not of an age but for all time!

And all the Muses still were in their prime,

When, like Apollo, he came forth to warm

Our ears, or like a Mercury to charm!

Nature her selfe was proud of his designes,

And joy'd to weare the dressing of his lines!

Which were so richly spun, and woven so fit,

As, since, she will vouchsafe no other Wit.

The merry Greeke, tart Aristophanes,

Neat Terence, witty Plautus, now not please;

But antiquated, and deserted lye

As they were not of Natures family.

Here the distinctive lines are “Nature her selfe was proud of his designes, And joy'd to weare the dressing of his lines! Which were so richly spun, and woven so fit.” Jonson wants us to find the reference to verse as clothing in Meres. There is one passage that fits, immediately preceding the section of comparisons, “As a long gowne maketh not an Advocate, although a gowne be a fit ornament for him: so riming nor versing maketh a Poet, albeit the Senate of Poets hath chosen verse as their fittest rayment; but it is yt faining notable images of vertues, vices, or what else, with that delightfull teaching, which must bee the right describing note to knowe a Poet by.” which Meres ascribes to “Sir Philip Sidney in his Apology for Poetry”.

Shakespeare’s Pronouns

Notice Jonson’s change of pronouns, from second person familiar thee to third person, he. “He” is Philip Sidney, and the author, Mary (thee), was “Sidney’s sister” in the elegy which graces her tomb[20]. The distinction was not lost on Michael Drayton. In his Letter to Henry Reynolds, Esq. Drayton characterized all the important English writers up to his time. All but one are referred to with the third person masculine he and his; Shakespeare alone is addressed with the non-gendered thou and thy.[21]

For all the praise heaped upon Mary Sidney, it was her brother who was owed homage by “all scenes of Europe,” a debt paid with Sonnets from authors across the continent after his heroic death fighting the Spanish at Zutphen. In the literary allusions of the period, he was Phoebus and Mary Pallas, the Apollo and spear shaking Minerva of their literary world. Thomas Nashe’s introduction to Philip’s Astrophil and Stella provides but one example to which Jonson could refer:

Apollo hath resigned his Iuory Harp vnto Astrophel, & he, like Mercury, must lull you a sleep with his musicke. . . fayre sister of Phœbus, and eloquent secretary to the Muses, most rare Countesse of Pembroke, thou art not to be omitted, whom Artes doe adore as a second Minerua, and our Poets extoll as the Patronesse of their inuention; for in thee the Lesbian Sappho with her lirick Harpe is disgraced, and the Laurel Garlande which thy Brother so brauely aduaunst on his Launce is still kept greene in the Temple of Pallas.[22].

In Nashe’s dedication Philip appears as both Mercury and Phoebus and Mary as Pallas Athena, the Spearshaking patron of warriors and poets who disgraces “Lesbian Sappho.” In To Penshurst, Jonson himself proclaims Philip’s “great birth where all the Muses met,” echoing the verses contributed by his mentor William Camden to the Oxford Memorial volume for Sidney published a year after Philip’s death. Camden’s Latin verse translated provides, “Nature’s genius admired herself in Sidney,” “when you were alive the Muses hoped to live,” and concludes, “Our Britain is the glory and jewel of the world, but Sidney was the jewel of Britain.”

The extended Sidney family, Robert, the Earl of Leicester, his daughter Mary Sidney Wroth, Robert’s nephew William Herbert Earl of Pembroke and Lord Chamberlain, and Robert’s sister and William’s mother Mary Sidney Herbert were key patrons and friends throughout Jonson’s life. He lauded them as subjects of some of his greatest poetry and dedicated to them even more of his work. The writers Meres’ cites as the best of ancient Rome and Greece are antiquated and deserted in comparison to Mary and her family amongst whom Jonson was proud to claim a place.

Once again we can examine the text for the embedded anagrams Jonson uses to reveal his intertextual references. He signals the covert naming of the author with the phrase Thou art in the text. Thou art leads to the anagram Mary (coincident with the overt Monument without a tomb), and in the next line and art precedes the anagram Sidney. Later, Jonson confirms the overt allusions to Meres with anagrams, five times naming Fr. Meres as source for the text (and rhyming his name for good measure). There is a sixth Meres anagram in the following section.

Thou art a [Moniment, without a tombe, [Mary]

And art alive [still, while thy] Booke doth live, [Sidney]

And we have wits to read, and praise to give.

That I not mixe thee so, my braine excuses ;

I meane with great, but disproportion'd Muses :

[For, if I thought my judgement were of yeeres], [Fr Meres]

I should commit thee surely with thy peeres,

And tell, how farre thou dist our Lily out-shine,

Or sporting Kid or Marlowes mighty line.

And though thou hadst small Latine, and lesse Greeke,

[From thence to honour thee, I would not seeke [Fr Meres]

For names]; but call forth thund'ring Aeschilus,

Euripides, and Sophocles to vs,

Paccuvius, Accius, him of Cordova dead,

To life againe, to heare thy Buskin tread,

And shake a stage: Or, when thy sockes were on,

Leave thee alone, for the comparison

Of all, that insolent Greece, or haughtie Rome

Sent forth, or since did [from their ashes] come. [Fr Meres]

Tri'umph, my Britain, thou hast one to show

To whom all scenes of Europe homage owe.

He was not of an age but [for all time! [Fr Meres]

And all the Muses] still were in their prime,

When, like Apollo, he came [forth to warm [Fr Meres]

Our ears], or like a Mercury to charm!

Nature her selfe was proud of his designes,

And joy'd to weare the dressing of his lines!

Which were so richly spun, and woven so fit,

As, since, she will vouchsafe no other Wit.

The merry Greeke, tart Aristophanes,

Neat Terence, witty Plautus, now not

please; But antiquated, and deserted lye

As they were not of Natures family.

Jonson’s choice of Meres and these specific passages has particular relevance to both Sidney and Shakespeare. Taken together these three passages uniquely identify the author as the “subject of all verse,” the learned Countess of Pembroke, Mary Sidney Herbert, Sidney’s sister. Pembroke’s mother, just as she is identified on the sable marble which marks her tomb in Salisbury Cathedral on the bank of the Wiltshire Avon near her Wilton home. Meres’ Palladis Tamia was the first printed acknowledgement that William Shakespeare was responsible for the plays previously attributed only to the company that performed them (Originally Pembroke’s Men, later, Sussex’, Derby’s, or the Lord Chamberlain’s as their patronage evolved). Shakespeare responded just months later with a scene in Henry IV, the second play published bearing the name. The connections revealed in both the Jonson and Shakespeare references suggest that Meres himself intended readers to make the connection between Shakespeare and Sidney, which itself has important implications for our understanding of relationships between early modern writers and their readers.

In line 24 of his poem Jonson says “we have wits to read and praise to give.” Having read Wits Treasury we will next see Jonson reference praise not for Shakespeare, but for Mary Sidney Herbert, drawn from published dedications by Christopher Marlow, Samuel Daniel and Michael Drayton in the final section of the poem.

Continue reading: Sweet Swan of Avon

[1] daxelrod, “The Shakespeare First Folio (Folger Copy No. 68),” Text, December 20, 2015, https://www.folger.edu/the-shakespeare-first-folio-folger-copy-no-68.

[2] Ben Jonson’s 1616 Folio (Newark : University of Delaware Press ; London ; Cranbury, NJ : Associated University Presses, 1991), http://archive.org/details/benjonsons1616fo0000unse.

[3] Francis Meres, Palladis Tamia Wits Treasury Being the Second Part of Wits Common Wealth. By Francis Meres Maister of Artes of Both Vniuersities., 2011, http://name.umdl.umich.edu/A68463.0001.001.

[4] mcarafano, “Publishing Shakespeare,” Text, December 15, 2014, https://www.folger.edu/publishing-shakespeare.

[5] Meres, Palladis Tamia Wits Treasury Being the Second Part of Wits Common Wealth. By Francis Meres Maister of Artes of Both Vniuersities., 283.

[6] TW Baldwin, William Shakespeare"s Small Latin and Lesse Greek (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1944).

[7] Meres, Palladis Tamia Wits Treasury Being the Second Part of Wits Common Wealth. By Francis Meres Maister of Artes of Both Vniuersities., 284.

[8] Meres, Palladis Tamia Wits Treasury Being the Second Part of Wits Common Wealth. By Francis Meres Maister of Artes of Both Vniuersities.

[9] J. E. Spingarn, A History of Literary Criticism in the Renaissance (Columbia University Press, 1908), https://doi.org/10.7312/spin90096.

[10] Meres lists Scaliger as one of two noteworthy literary critics.

[11] “Cornelia,” accessed January 24, 2023, https://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/eebo/A01500.0001.001?view=toc.

[12] The Tragedy of Cleopatra in John Pitcher, Samuel Daniel, vol. 1 (Oxford University Press, 2017), https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199935338.013.88.

[13] Seneca, “Of Consolation: To Marcia” (n.d.), Wikisource.

[14]“In_the_name_of_sappho_-_reception_of_sappho_and_her_influence_on_the_female_voice_in_hellenistic_epigram.Pdf,” accessed September 7, 2022, https://www.ed.ac.uk/files/atoms/files/in_the_name_of_sappho_-_reception_of_sappho_and_her_influence_on_the_female_voice_in_hellenistic_epigram.pdf.

[15] R.J.H. Matthews, “The Lament For Adonis : Questions Of Authorship,” Antichthon 24 (1990): 32–52, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0066477400000526.

[16] William Bellamy, Shakespeare’s Verbal Art (Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2016).

[17] “Henry IV, Part 1, Act 2, Scene 4 | The Folger SHAKESPEARE,” February 7, 2019, https://shakespeare.folger.edu/shakespeares-works/henry-iv-part-1/act-2-scene-4/.

[18] “Henry IV, Part 1 (Quarto 1, 1598) :: Internet Shakespeare Editions,” accessed January 24, 2023, https://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/doc/1H4_Q1/scene/2.4/index.html.

[19] Ibid.

[20] “Mary Sidney Herbert (1561-1621) - Find a Grave...,” accessed January 24, 2023, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/16732373/mary-herbert. The current stone itself is a modern addition. The elegy appears in manuscript in Jonson’s papers and was attributed to him until an early 20th century monograph awarded it to William Browne, primarily on the basis that Jonson was not close to Mary Sidney and her family, a judgement which probably warrants reexamination.

[21] “King’s Collections : Exhibitions & Conferences : Michael Drayton on Shakespeare,” accessed January 24, 2023, https://kingscollections.org/exhibitions/specialcollections/the-very-age-and-body-of-the-time-shakespeares-world/what-revels-are-at-hand-shakespeares-literary-contemporaries/michael-drayton-on-shakespeare.

[22] “Front Matter. Sir Philip Sidney (1554-1586). Astrophel and Stella. Seccombe and Arber, Comps. 1904. Elizabethan Sonnets,” accessed January 24, 2023, https://www.bartleby.com/358/1.html.

So, the question I have is that if Jonson wanted to identify Mary Sidney as the "real" Shakespeare, why didn't he just do that? She's been a published playwright since 1595 and by 1623 there's no reason on earth that I can see why she wouldn't be able to accept praise for authoring all the plays in the folio. Why would Jonson find it necessary to indulge in such a fantastic game of literary hide and seek?